The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) released its proposal for small unmanned aircraft (UAS) remote identification rules, a critical step to safely integrating drones into the national airspace and unlocking advanced operational capabilities.

The agency expects these rules to go into effect three years after the effective date of a final rule, which was estimated earlier this year to be 24 months away.

Translation: It may be five years before remote ID is fully implemented — a timeframe that could have significant impact on operators’ ability to safely fly beyond their visual line of sight, which will be necessary for large-scale drone delivery or the use of low-altitude air taxis for urban air mobility services.

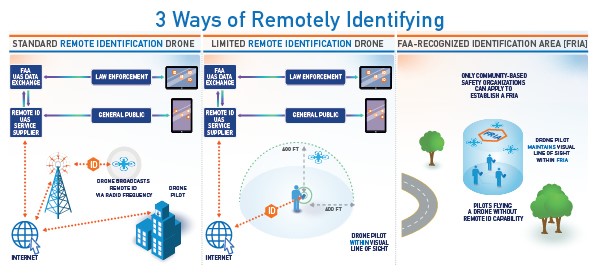

The FAA is proposing three methods of meeting remote ID compliance: standard identification; limited identification; or an “FAA-recognized identification area.” Limited identification requires the operator to only broadcast his or her location, but restricts operations to within 400 feet. Compliance through an FAA-recognized identification zone allows communities to apply to establish such an area, where pilots can fly without remote ID capabilities, though they are restricted to maintaining visual line of sight.

Standard remote identification — the main method of compliance for unmanned aircraft — will require the following message elements:

UAS Identification: This requirement can be met either through a serial number assigned to the drone by the manufacturer, or a ‘session identification number’ assigned by a remote ID unmanned service supplier (USS), referring to UAS companies such as Kittyhawk.io, Altitude Angel, AirMap and others.

The second option — a session ID provided by a remote ID USS — allows for greater operator privacy by publicly masking the operator’s identity and links between repeated flights by the same operator.

“The association between a given session ID and the unmanned aircraft serial number would not be available to the public through the broadcast message,” the FAA’s proposed rule states.

Control Station Location: UAS will have to transmit the location of their control station, which the rule requires to be co-located with the person manipulating its flight controls. Latitude and longitude as well as barometric altitude must be included in the message, with the type of position source for the former not specified at this time to allow for flexibility to designers and producers of UAS, according to the FAA. The rule does not require a secondary geometric measurement of altitude in addition to a barometric reading.

It is also notable that Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) equipment, used commonly by manned aircraft, cannot be used to comply with broadcast remote ID requirements under the proposed rule, with the FAA citing the “lack of infrastructure for these technologies at lower altitudes and the potential saturation of available radio frequency spectrum.”

Aircraft Location: Drones will be required to transmit the same location as their control stations, meaning latitude and longitude as well as barometric altitude. This can be avoided through the limited remote ID compliance option, which then restricts operations to within 400 feet of the operator.

Time Mark: Drones will be required to transmit a time mark for both the UAS and the control station location, with the former excluded under limited remote ID compliance. As the drone or control station positions change, the position source — such as a GPS receiver — should provide continuous outputs indicating the new position.

Indication of Emergency Status: The final element of the remote ID message will indicate if the aircraft is experiencing an emergency, such as a lost connection or a downed aircraft. This can be initiated manually by the operator or automatically by the UAS, depending on the nature of the emergency and the drone’s capabilities, according to the FAA’s proposed rule.

Excluded from the remote ID requirement are amateur-built UAS, “UAS of the United States government,” which is not clarified further, and small unmanned aircraft under 0.55 lbs — meaning DJI’s Mavic Mini, released earlier this fall, will not be affected. China-based DJI’s small UAS make up around 80 percent of the commercial market.

Under the proposed rule, UAS will be required to both broadcast these message elements directly from the unmanned aircraft and simultaneously transmit that same information to a remote ID USS via internet connection. The FAA-recognized compliance zones and limited remote ID methods of compliance are to accommodate operators who wish to avoid networked transmission and instead rely solely on broadcast identification and location. If connection is lost, the operator is expected to land the aircraft as soon as possible.

“For both standard and limited remote identification UAS, at this time the FAA has not proposed any requirements regarding how the UAS connects to the internet to transmit the message elements or whether that transmission is from the control station or the unmanned aircraft,” the proposed rule states.

As currently written, the proposed rule would avoid imposing additional hardware or connectivity-related costs on the industry by allowing the internet connection to be maintained from the control station rather than the unmanned aircraft — a topic that has been hotly debated within the commercial drone world.

ADS-B Out equipment cannot be used to comply with broadcast remote ID requirements under the proposed rule, with the FAA citing the “lack of infrastructure for these technologies at lower altitudes and the potential saturation of available radio frequency spectrum.”

The inclusion of location information for both a drone and its operator are critical for law enforcement seeking to more quickly and appropriately respond to safety or security risks posed by unmanned aircraft.

Discussing of the costs and benefits involved in remote ID requirements, the FAA’s proposed rule cites the provision of “airspace awareness to the FAA, national security agencies, and law enforcement entities … this information could be used to distinguish compliant airspace users from those potentially posing a safety or security risk, fulfilling a key requirement for law enforcement and national security agencies charged with protecting public safety.”

Law enforcement officials have struggled to effectively match rogue unmanned aircraft with their operators — a problem many believe federally-mandated remote ID requirements will help address. Since April 2016, Los Angeles International Airport has documented 205 reports of drone activity near the airport, but was only able to identify and contact the operator of the drone in one instance, according to Los Angeles World Airports Authority CEO Deborah Flint. Drone sightings close to the runway at London’s Gatwick Airport in December 2018 famously caused the cancellation of hundreds of flights, affecting approximately 140,000 passengers.

“The FAA envisions it would facilitate near real-time access to the remote identification message elements (paired with certain registration data, when necessary) for accredited and verified law enforcement and federal security partners,” the proposed rule states. “This information could be used to identify and possibly contact the person manipulating the flight controls of a UAS in response to potentially unsafe or nefarious UAS activities.”

“Remote identification information, when correlated with UAS registry information, would inform law enforcement officers about two essential factors: who registered the UAS, and where the person manipulating the flight controls of a UAS is currently located,” the rule adds.