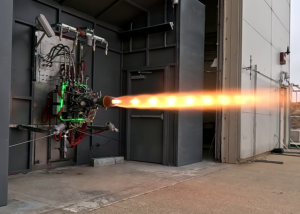

Engine developer and manufacturer Ursa Major has hot-fired its new Draper liquid engine dozens of times since the first test in early March, a strong early endorsement of the performance and reliability of the 4,000-pound thrust powerplant that the company touts as well suited for hypersonic defense and target applications, and for in-space propulsion. The 50-plus hot-firings of the first test article at Ursa Major’s headquarters north of Denver in Berthoud, Colo., have occurred under a year-old contract with the…

By

By