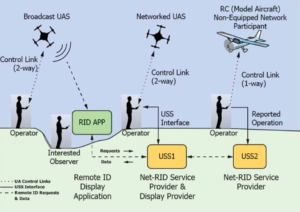

The Federal Aviation Administration is working through more than 53,000 comments on its proposed approach to remote identification for remote aircraft and hopes to issue a final ruling before the end of the year, according to FAA administrator Stephen Dickson — although that timeline will likely be affected by the global coronavirus outbreak. Police departments, the Department of Homeland Security and other agencies are watching this space intently, ramping up investment into analysis of more than 500 drone security products…

By

By