A top House Armed Services Committee member this week argued the Defense Department’s top line budget process that divides funding among the services constrains the ability of the Navy to build a larger fleet.

“I feel that…it’s all constrained by this process of a top line. This is what you got to fit into that top line. So that’s the only thing that the Navy feels they can come to Congress and say, this is what we need,” Rep. Elaine Luria (D-Va.), vice chair of the House Armed Services Committee and member of the Seapower subcommittee, said during a virtual Defense One

event on Sept. 14.

Luria said she believes there needs to be a clear prioritization for the administration for the larger Navy if the Defense Department wants to increase the size of the fleet, as Congress has directed them, with a goal of at least 355 manned ships.

“It doesn’t just start with the Navy, I think it starts higher than that. When we look in how the defense budget comes about, there’s a top line that kind of gets split in the Pentagon, to way over simplify it, split into pieces of the pie, thirds. And the Navy – this is what they’ve got and the Navy and Marine Corps have to divvy that up.”

Luria said the Navy’s works from a perspective that that is the top line budget they have and “it comes to Congress and says – well, this is the best we can ask for with what we think you’re going to give us.”

However, she said they should reverse the process and start from what the Navy’s clear objective is based on the global situation, what is needed to credibly deter China from using force against Taiwan, and other critical U.S. needs internationally.

“And then from those requirements, the [Program Objective memorandum] and the budget, I think it’s all backwards.”

Luria argued this should be an objective from the “very top of the administration, the president,” comparing it to when the Reagan administration decided to build out a 600-ship Navy.

“When we said we were going to build a 600-ship Navy, we built a 600-ship Navy. The entire country understood and it was clearly communicated why that was important in order to defeat the Soviet Union. I think that we need that solid backing.”

She said the government can have different plans about the exact number of ships, “but the real thing is that none of these plans that the Navy has brought to us have really come with that justification of: here’s what we need to do it, here’s what we need to do, this is the fleet we need to build, here’s why we need to build it, and here’s the risk if we don’t do it.”

Luria said she has been waiting for four years and each budget cycle “for someone to come and tell Congress – this is what we think we’re going to get but like, here’s what we really need. And here’s why we need it. And this is the threat posed by China. This is the number of ships we need to build.”

Luria thinks much is getting lost in translation in the sense of urgency from combatant commanders in the Pacific to topline budgets and numbers.

“The combatant commanders in the Pacific theater who day in, day out deal with these interactions with China’s aggression against Taiwan, it’s really like a gray zone conflict going on day after day, and what they need to respond to that and we should be prioritizing based off the strategy and their top priorities, to make sure that our investments are aligned there. So I think it’s a lot bigger than just focusing on the number. I think it’s really taking a step back and looking at our broad national defense priorities.”

Luria argued this means the Defense Department should devote more resources to the Navy and Air Force than the Army currently, as opposed to the current status quo that roughly divides the services into thirds each.

“I don’t think we need a standing army of 485,000 right now in light of the threats that we see in the Pacific and our constrained resources.”

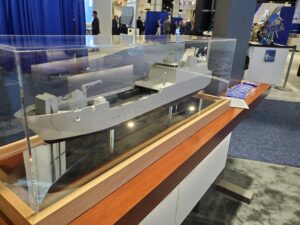

Relatedly, Luria said she thinks the Navy has pulled back the Marine Corps’ Light Amphibious Warship (LAW) due to limited funding. The Marine Corps wants to procure up to 35 of these smaller vessels to transport upward of 75 Marines up to 3-4,000 miles and carry 8-10,000 square feet of cargo space to support the Marine Littoral Regiment.

She said from her perspective “we were eager to go ahead and fund that. And there are many shipyards, for example in the Gulf Coast, that could build something of that size and complexity. Yet, it’s constantly being scaled back or pulled back or delayed, from my perspective, by the Navy. So if the Navy was more forward leaning, I truly believe that Congress would be behind that.”

Luria said programs like the LAW are important to help expand the shipbuilding industrial base from focusing exclusively on the current high-end complex platforms built by larger shipyards General Dynamics Bath Iron Works [GD] in Bath, Maine; HII’s Ingalls Shipbuilding [HII] in Pascagoula, Miss., and HII’s Newport News Shipbuilding in Virginia to include smaller and medium-sized shipbuilders as well.

In 2021, USNI News reported the Navy awarded concept design contracts to Fincantieri Marinette Marine, Austal USA, VT Halter Marine, Bollinger and TAI Engineers worth under $7.5 million total with an option for preliminary design work ahead of design selection.