The White House this week said while it generally supports the House’s fiscal year 2022 defense authorization bill, it opposes funding for older platforms that cannot be affordably modernized.

“The Administration opposes the direction to add funding for platforms and systems that cannot be affordably modernized given the need to prioritize survivable, lethal, and resilient forces in the current threat environment and eliminate wasteful spending. Our national security interests require forces that can fight across the spectrum of conflict,” said an Office of management and Budget (OMB) statement of administration policy published Sept. 21.

The White House specifically opposes restoring funding to programs OMB said limit the Defense Department’s “ability to divest or retire lower priority platforms not relevant to tomorrow’s battlefield.”

This includes opposing language limiting retirement or inactivation of Ticonderoga-class cruisers as well as minimum inventory requirements for systems like the KC-10 and tactical airlift aircraft.

The document argued that “the President’s Budget divests or retires vulnerable and costly platforms that no longer meet mission or security needs, and reinvests those savings in transformational, innovative assets that match the dynamic threat landscape and advance the capabilities of the force of the future.”

The original budget request sought funds to retire five cruisers in FY ‘22 as previously planned and add two more, the USS Hue City (CG-66) and USS Anzio (CG-68). The Navy argued cruiser modernization costs grew over 200 percent more than initially planned and retiring CG-66 and CG-68 would save up to $469 million (Defense Daily, May 28).

The House bill currently only allows DoD to retire or inactivate four of the seven total planned cruisers the Navy wanted to retire: CG-66, the USS Vela Gulf (CG-72), USS Port Royal (CG-73), and CG-68.

OMB said the language related to these systems “would limit the Department’s flexibility to prioritize resource investment, delay modernization of capabilities, and impede implementation of the National Defense Strategy.”

The administration also “strongly encourages” Congress to remove a statutory cap on the number of used sealift vessels the Defense Department can procure and remove a statutory link between using the National Defense Sealift funding to purchase used vessels and the requirement to procure new construction ships.

“This will allow the Administration to recapitalize the sealift fleet, with all used ship conversions in U.S. shipyards, for a fraction of the cost of procuring new vessels,” the statement said.

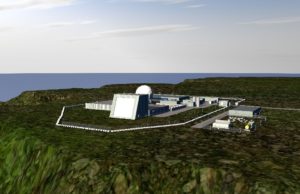

Separately, the White House said it strongly opposes a requirement to certify funding for the Homeland Defense Radar-Hawaii (HDR-H) because Hawaii is currently defended against missile threats like the rest of the U.S. and DoD is investing in capabilities like the Next Generation Interceptor (NGI).

DoD has not sought funding for the HDR-H for two years, since it requested $275 million in the FY ‘20 budget. At that time, the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) expected the HDR-H to finish development and initial fielding by FY ‘23 and planned to request military construction funds in FY ‘21 to last from 2021-2022 (Defense Daily, March 12, 2019).

Plans changed in the FY ‘21 budget request that zeroed out funds for the program.

In June, MDA Director Vice Adm. Jon Hill spoke to the utility of adding HDR-H in the future. He said while the current sensor architecture can defend Hawaii today, as the ballistic missile threat gets more complex, discrimination is more important and it will become harder to maintain a track on threat missiles without a sensor based in Hawaii (Defense Daily, June 24).

The White House admitted the DoD planned to field HDR-H, another Pacific Radar, the Redesigned Kill Vehicle (RKV) and Long Range Discrimination Radar in Alaska by the mid-2020s “ as a system of systems to improve homeland ballistic missile defense.”

However, the statement said the Pacific Radar has been delayed indefinitely due to stalled negotiations with the unnamed host nation, and the RKV program has been canceled and replaced with the NGI.

“Hawaii is currently defended against missile threats to the same extent as the rest of the United States, and DoD is currently investing in other capabilities, such as the Next Generation Interceptor, which will support the long-term defense of Hawaii,” the White House said.

The administration also opposes provisions it said would prejudge the outcome of the Nuclear Posture Review currently underway. This includes sections that prohibit funding for extending the service life of the B83-1 nuclear gravity bomb, restrictions on changing intercontinental ballistic missile alert levels or the number of deployed ICBMs, and a prohibition on reconverting or retiring the low-yield W76-2 warhead.

Other provisions the administration opposes include the creation of a Space National Guard, which it argued would create a new bureaucracy estimated to cost up to $500 million per year; designating a single combatant command to be responsible for global bulk fuel management and deliver; and requirements for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the U.S. STRATCOM Commander “to provide pre-decisional and deliberative materials associated with the Integrated Deterrence Review, as well as the Nuclear Posture Review and Missile Defense Review” because they encroach on constitutional prerogatives of the president.